1. Eukaryotic Gene Expression: an introduction

In the last tutorial, we learned about bacterial gene regulation through operons. These systems allow organisms like E. coli to turn genes on and off in response to changes in their environments.

Now we’ll turn to gene regulation in multicellular eukaryotes. Start with the interactive reading below.

[qwiz qrecord_id=”sciencemusicvideosMeister1961-Eukaryotic Gene Regulation Intro (v2.0)”]

[h]Eukaryotic Gene Regulation: Interactive Reading

[i]

BioHaiku

All somatic cells

Descendants of one zygote

Yet so different!

[q labels = “top”]In a multicellular eukaryote, not all genes are active all the time. Complete the table below identifying which genes are active or inactive in each of these three cells.

[l]active

[fx] No, that’s not correct. Please try again.

[f*] Correct!

[l]inactive

[fx] No, that’s not correct. Please try again.

[f*] Great!

[q labels = “top”]Here’s a key idea from this module about eukaryotic gene regulation: Almost all of the cells in a multicellular eukaryotic organism are genomically _____________. They have (with only a few exceptions), the same sequence of DNA nucleotide _________.The differences in cell____________ and function are all about the different __________ that are____________ in different cells.

[l]genes

[fx] No. Please try again.

[f*] Excellent!

[l]equivalent

[fx] No, that’s not correct. Please try again.

[f*] Good!

[l]expressed

[fx] No. Please try again.

[f*] Great!

[l]structure

[fx] No, that’s not correct. Please try again.

[f*] Great!

[l]bases

[fx] No, that’s not correct. Please try again.

[f*] Good!

[q]What is genomic equivalence? Again, it means that almost all cells in a multicellular eukaryote, because they’re descendants of the same zygote, have the same genes, which are encoded in [hangman].

To connect this to what you just did in the first card in this stack, nerve cells (like all cells) have to do the basic work of staying alive and making ATP: that’s why their genes for breaking down sugar through processes such as [hangman] (the first phase of respiration) are active, just as they were in all the other cells. But of the cells listed, the only one that was involved in blood sugar regulation was a pancreatic cell, which has to churn out the blood-sugar-lowering hormone [hangman].

Again, almost all cells are genomically equivalent. What makes them different are the different genes that they [hangman].

[c]RE5B[Qq]

[c]Z2x5Y29seXNpcw==[Qq]

[c]aW5zdWxpbg==[Qq]

[c]ZXhwcmVzcw==[Qq]

[q]But why “almost all cells.” Because some cells, like gametes, are haploid, with a unique combination of genes that results from meiosis. Other cells, like red blood cells, have no genes at all. Yet others (like antibody-making cells in the immune system) develop in ways that increase their mutation rate, or swap portions of genes as a strategy for increasing molecular diversity.

[q]Now that we’ve noted the few exceptions to the rule of genomic equivalence, we can address the central question of this and the next few tutorials: How, as a member of a team of trillions of other cells, does any one cell in a multicellular eukaryotic organism know which genes to turn on, and which to leave turned off. How are eukaryotic genes regulated?

[/qwiz]

2. Gene regulation through DNA/chromatin packaging

In the previous section, we established that the cells making up different tissues in a multicellular eukaryote — a human being, a Dungeness crab, or the wildflower known as Queen Anne’s Lace — are genomically equivalent. They have the same DNA. The phenotypic differences between the muscle tissue, nerve tissue, and skin tissue in an animal are about which genes are expressed in these tissues.

Much of these differences in gene expression can be explained through epigenetics. The prefix “epi” means above or in addition to. Epigenetic changes are modifications to genes (and the entire genome) that occur above the level of DNA. They don’t involve changes in DNA sequences, but in how the DNA is packaged within a cell’s nucleus.

DNA packaging reflects an issue in eukaryotes that’s absent from prokaryotes like E. coli. Whereas the genome of E. coli consists of about 4.9 million base pairs, the human genome consists of two sets of chromosomes, each of which consists of 3.2 billion nucleotides, for a total human genome size of 6.4 billion nucleotides. If you were to stretch out all of the DNA in each of your 46 chromosomes and lay that DNA end to end, each cell would have about two meters of DNA. The diameter of the nucleus of a cell is about 6 µm (millionths of a meter). So, two meters of DNA have to be condensed into very little space. How can so much DNA get stuffed into the nuclei of each and every one of the cells within our bodies? And how can this be done in a way in which the genes that need to be accessed in a particular tissue type are easily available?

One way is by tightly packing up the DNA that’s not needed while leaving the DNA that is needed for specifying the proteins in a particular tissue in a looser, more accessible configuration.

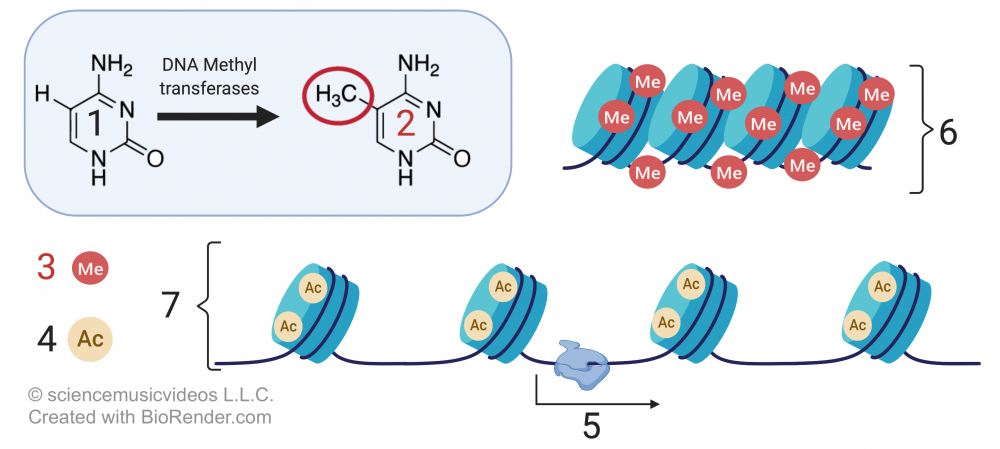

This level of DNA packaging is just out of the range of what you’d see in a typical AP Bio lab where you use a microscope to look at human cheek cells (possibly yours). If your technique is good, you’ll see what’s shown on the left. There will be a clearly defined nucleus (2), with a dark spot (the nucleolus) often visible.

This level of DNA packaging is just out of the range of what you’d see in a typical AP Bio lab where you use a microscope to look at human cheek cells (possibly yours). If your technique is good, you’ll see what’s shown on the left. There will be a clearly defined nucleus (2), with a dark spot (the nucleolus) often visible.

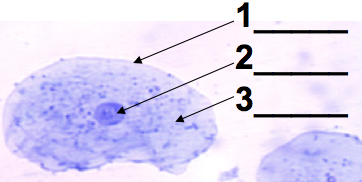

With a higher-resolution image, you can see a lot more structure in the nucleus. In the image at right, “1” is the nuclear membrane. Number 2 is lightly staining nuclear material called euchromatin. The darker areas at 3 are called heterochromatin. Number “4” is the nucleolus, the site of ribosome assembly.

With a higher-resolution image, you can see a lot more structure in the nucleus. In the image at right, “1” is the nuclear membrane. Number 2 is lightly staining nuclear material called euchromatin. The darker areas at 3 are called heterochromatin. Number “4” is the nucleolus, the site of ribosome assembly.

The connection with DNA packaging and gene regulation is this: heterochromatin is tightly coiled DNA that’s unavailable for transcription. Euchromatin is less coiled (or uncoiled), and can be transcribed into RNA, which can then be translated into protein.

In the context of DNA, what does coiling mean? To fit two meters of DNA inside a cell’s nucleus in an organized way, eukaryotes wrap their DNA around proteins called histones.

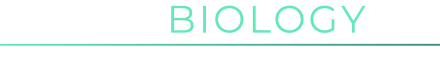

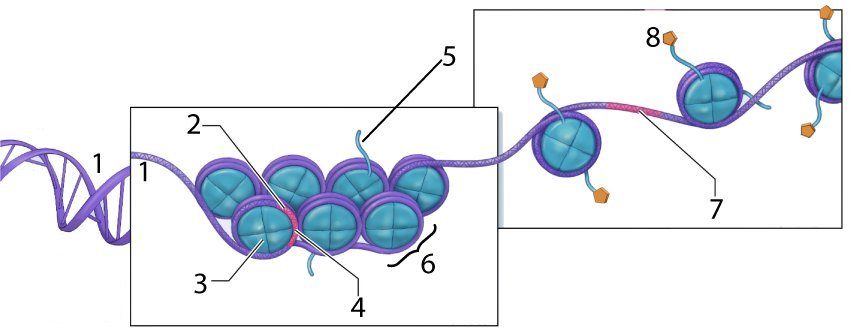

In the diagram above, the DNA is shown at “1.” At “2” we have a gene, but it’s wrapped up so tightly that it’s unavailable for transcription (with “4” representing such untranscribable DNA). Number “6” is a nucleosome, a “bead” consisting of several linked histone proteins (one of which is indicated by “3”).

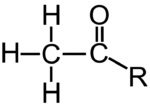

Various molecules can interact with histones in a way that affects the density of DNA packaging. One of these, an acetyl group (structural formula on the left), is shown at “8” above. The acetyl groups bind to the tails (“5”) of the histone molecules in a process called acetylation. Acetylation causes the DNA to uncoil, making genes available for transcription (with one such transcribable gene shown at 7).

Methylation, which involves adding a methyl group to either DNA or a histone protein, has the opposite effect. Methylation silences genes, organizing chromatin into a more compact form that doesn’t allow genes to be transcribed.

In the image that’s above and to the right,

- “1” is the nucleotide base cytosine.

- “2” shows cytosine with a methyl group (—CH3) attached).

- “3” indicates methyl groups attached to DNA.

- “4” represents acetyl groups.

- “6” shows compact DNA (heterochromatin), unavailable for transcription.

- 7 shows relaxed DNA (euchromatin), with genes available for transcription (“5”).

Methylation and acetylation are two of the key processes involved in tissue differentiation within a multicellular eukaryote. While what follows is a bit of an oversimplification, a good model for explaining the many differences between your muscle cells and the cells that make up the lens of your eye is this:

- In a muscle cell, all of the genes that are not involved with muscle contraction — genes for neurotransmitters, or for stomach enzymes, or for hair production, or making eye lens proteins — are methylated, and tightly coiled up as heterochromatin. The muscle cell genes are acetylated euchromatin, and available for transcription.

- In the cells in the lens of your eye, muscle cell protein genes, stomach enzyme genes, hair production genes, and neurotransmitter genes are methylated and coiled up as heterochromatin. The eye lens genes are acetylated as euchromatin and are available for transcription.

3. Euchromatin, Heterochromatin, Methylation, Acetylation: Checking Understanding

[qwiz qrecord_id=”sciencemusicvideosMeister1961-DNA Packaging (v2.0)”]

[h]DNA packaging

[i]

[q labels = “top”]

[l]Acetyl group

[fx] No, that’s not correct. Please try again.

[f*] Correct!

[l]DNA

[fx] No. Please try again.

[f*] Excellent!

[l]histone

[fx] No, that’s not correct. Please try again.

[f*] Great!

[l]histone tail

[fx] No. Please try again.

[f*] Excellent!

[l]nucleosome

[fx] No. Please try again.

[f*] Correct!

[l]Transcribable DNA

[fx] No. Please try again.

[f*] Excellent!

[l]Untranscribable DNA

[fx] No. Please try again.

[f*] Correct!

[q labels = “top”]

[l]euchromatin

[fx] No. Please try again.

[f*] Excellent!

[l]heterochromatin

[fx] No, that’s not correct. Please try again.

[f*] Great!

[l]nuclear membrane

[fx] No. Please try again.

[f*] Excellent!

[l]nucleolus

[fx] No, that’s not correct. Please try again.

[f*] Correct!

[q labels = “top”]

[l]active/transcribed DNA

[fx] No. Please try again.

[f*] Correct!

[l]inactive/untranscribed DNA

[fx] No. Please try again.

[f*] Correct!

[l]ribosome assembly site

[fx] No. Please try again.

[f*] Great!

[l]RNA must cross this to be transcribed

[fx] No. Please try again.

[f*] Correct!

[q labels = “top”]

[l]Acetyl group

[fx] No. Please try again.

[f*] Good!

[l]histone

[fx] No. Please try again.

[f*] Excellent!

[l]histone tail

[fx] No, that’s not correct. Please try again.

[f*] Great!

[l]methyl group

[fx] No. Please try again.

[f*] Correct!

[l]Transcribable DNA

[fx] No, that’s not correct. Please try again.

[f*] Great!

[l]Untranscribable DNA

[fx] No, that’s not correct. Please try again.

[f*] Good!

[q labels = “top”]

[l]acetyl group

[fx] No, that’s not correct. Please try again.

[f*] Excellent!

[l]euchromatin

[fx] No, that’s not correct. Please try again.

[f*] Excellent!

[l]heterochromatin

[fx] No, that’s not correct. Please try again.

[f*] Great!

[l]methyl group

[fx] No, that’s not correct. Please try again.

[f*] Great!

[l]RNA polymerase

[fx] No. Please try again.

[f*] Great!

[q]The differences between muscle tissue and eye-lens tissue are not about differences in the [hangman] in these tissues. That’s because almost all cells in a eukaryotic organism are genomically [hangman]. The difference, in other words, isn’t genetic, but [hangman].

[c]RE5B[Qq]

[c]ZXF1aXZhbGVudA==[Qq]

[c]ZXBpZ2VuZXRpYw==[Qq]

[/qwiz]

4. Heterochromatin, Barr Bodies, and Tortoiseshell Cats

Unless you’re a cat fanatic, you probably didn’t know that the fur coloration pattern called tortoiseshell is almost entirely limited to females. Explaining this involves using many of the concepts introduced above (euchromatin, heterochromatin, and their molecular connections with acetylation and methylation).

In mammals, sex determination works through an XX, XY system (click here for a review). A female mammal has two X chromosomes in each of her somatic cells. By contrast, a male mammalian somatic cell has an X chromosome and a Y chromosome. If you think of the central dogma of molecular genetics —DNA makes RNA makes protein — that means that you’d expect a cell of a given tissue type in a female’s body to have twice as much RNA and protein produced for any gene on the X chromosome as would a corresponding cell in a male’s body.

But that’s not the case.

The reason is that one of the copies of the two X chromosomes in every female cell is inactivated. This shutdown is referred to as dosage compensation: it ensures that for every gene on the X chromosome, the resulting amount (or dose) of the gene product (RNA and protein) is the same, whether or not that gene product is in a female cell or a male cell.

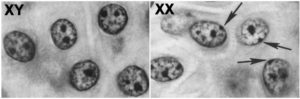

This inactivation happens early in embryonic development when the embryo has a relatively small number of cells. The inactivated X chromosome becomes a tightly coiled piece of heterochromatin, visible as a spot that can be seen toward the edge of the nucleus. It’s called a Barr body (named after its discoverer), and you can see these Barr Bodies (indicated by the arrows) in the image above and to the right.

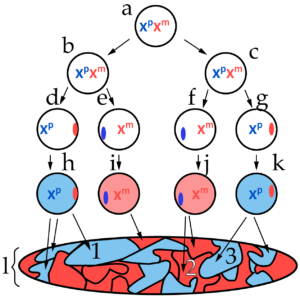

The diagram at left represents, in a schematic way, how X inactivation occurs within the body of a female mammal. This pattern was first discerned by British geneticist Mary Lyon in 1955, and you might see it referred to as lyonization.

The letter “a” represents the diploid zygote (fertilized egg cell), with two active X chromosomes. Xp represents the paternal X chromosome (the one inherited from the father) while Xm represents the maternal X chromosome.

Note that it’s not until the embryo has undergone a few rounds of cell division that one of the X chromosomes shuts down, becoming a Barr body. In the image at left, for example, cells “d” and “g” have an active paternal X chromosome, while the maternal X has become a Barr body (represented by the red oval on the right side of the circles that represent the nuclei of these cells). In cells “e” and “f,” the maternal chromosome is active, while the paternal chromosome has become a Barr body (represented by the blue ovals).

There are a few things to note about X inactivation

- It involves the methylation of both the DNA and the histone proteins of the inactivated chromosome.

- It’s random (and not necessarily 50/50 as shown above, though that’s usually the way it works out).

- Once an X chromosome has been inactivated, it stays that way through all subsequent cell divisions. In the diagram above, the letter “l” represents a cell map of the organism. Area 1 consists of all of the cells that descended from cell “h.” All of those cells have the same X inactivation pattern as cell “h,” with the paternal X chromosome active, and the maternal X silenced. All the cells in area 2, by contrast, descended from cell “j,” and have retained that cell’s X inactivation pattern.

The result is that females are developmental mosaics. A mosaic is an image created from pieces of tile, as shown in the image to the right. Because of X inactivation, females have patches of cells that have one or the other X chromosome active.

And that is how we get tortoiseshell cats.

And that is how we get tortoiseshell cats.

Please watch the short video below.

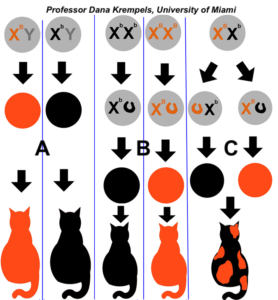

As you can see in the diagram on the right, males can’t be tortoiseshell (with one exception that we’ll address below). Males either express one fur color allele or the other, depending on what they inherit from their mother (as shown in the two columns labeled “A”). If females are homozygous (column B), they’ll also either be one color or the other.

Only female heterozygotes will be tortoiseshell, with some cells expressing the allele that’s on their maternal X chromosome, and other cells expressing the allele on their paternal X chromosome.

Note that calico cats add another level of complexity to this scheme. One autosomal allele codes for the presence or absence of color (think of the black-and-white pattern of the hair on the body of a cow). In the area with colored fur, X-inactivation results in patches with orange or black fur.

This same phenomenon of X-inactivation and female mosaicism applies in humans just as it does in cats. In humans, there’s a condition called hypohydrotic ectodermal dysplasia that involves abnormal development of sweat glands (and many other symptoms). Males who inherit this condition experience it all over their bodies. Females, because of X-inactivation, experience this condition in patches. Some skin will have normal sweat glands, while in other patches, the glands won’t function. Click here if you’re interested in learning more about this condition, and here for a detailed explanation of X inactivation, including a list of skin conditions linked to the X chromosome which express themselves in a mosaic pattern. Both links will open in a separate tab.

5. Barr Bodies, Female Mosaicism, Epigenetic Modification of DNA: Checking Understanding

[qwiz random = “true” qrecord_id=”sciencemusicvideosMeister1961-Barr Bodies, Female Mosaicism, and Heterochromatin (v2.0)”]

[h]Barr Bodies, Female Mosaicism, and Heterochromatin

[i]

[q] Tightly packed chromatin that’s unavailable for transcription is called [hangman].

[c]IGhldGVyb2Nocm9tYXRpbg==[Qq]

[f]IEdyZWF0IQ==[Qq]

[q] Loosely packed chromatin with DNA that can be transcribed is called [hangman].

[c]IGV1Y2hyb21hdGlu[Qq]

[f]IEdyZWF0IQ==[Qq]

[q] In the diagram below, which number is pointing to a histone?

[textentry single_char=”true”]

[c]ID M=[Qq]

[f]IEV4Y2VsbGVudC4gTnVtYmVyICYjODIyMDszJiM4MjIxOyBpcyBwb2ludGluZyB0byBhIGhpc3RvbmUu[Qq]

[c]IDc=[Qq]

[f]IFlvdSYjODIxNztyZSBleHRyZW1lbHkgY2xvc2UuICYjODIyMDs2JiM4MjIxOyBpcyBhIGdyb3VwIG9mIGhpc3RvbmVzIG9yZ2FuaXplZCBpbnRvIGEgbnVjbGVvc29tZS4gQ2hvb3NlIGEgbnVtYmVyIHRoYXQmIzgyMTc7cyBqdXN0IHBvaW50aW5nIHRvIG9uZSBoaXN0b25lLg==[Qq]

[c]ICo=[Qq]

[f]IE5vLiBIaXN0b25lcyBtYWtlIHVwIG51Y2xlb3NvbWVzIChzaG93biBhdCAmIzgyMjA7Ni4mIzgyMjE7KS4gVGhlIGhpc3RvbmVzIGhhdmUgdGFpbHMgKHNob3duIGF0ICYjODIyMDs1JiM4MjIxOykgdGhhdCBjYW4gYmUgdXNlZCB0byBtb2RpZnkgdGhlIGRlbnNpdHkgb2YgRE5BIHBhY2thZ2luZy4=[Qq]

[q] In the diagram below, which number is showing DNA that’s available for transcription?

[textentry single_char=”true”]

[c]ID c=[Qq]

[f]IEV4Y2VsbGVudCEgJiM4MjIwOzcmIzgyMjE7IHNob3dzIEROQSB0aGF0JiM4MjE3O3MgYXZhaWxhYmxlIGZvciB0cmFuc2NyaXB0aW9uLg==[Qq]

[c]IEVudGVyIHdvcmQ=[Qq]

[f]IE5vLCB0aGF0JiM4MjE3O3Mgbm90IGNvcnJlY3Qu[Qq]

[c]ICo=[Qq]

[f]IE5vLiBGaW5kIEROQSAoaW5kaWNhdGVkIGJ5ICYjODIyMDsxJiM4MjIxOykgdGhhdCYjODIxNztzICYjODIyMDtyZWxheGVkIGVub3VnaCB0byBiZSBhY2Nlc3NlZCBieSBtb2xlY3VsZXMgbGlrZSBSTkEgcG9seW1lcmFzZSwgbWFraW5nIHRyYW5zY3JpcHRpb24gcG9zc2libGUu[Qq]

[q] In the diagram below, which number is showing an acetyl group?

[textentry single_char=”true”]

[c]ID g=[Qq]

[f]IEdvb2Qgd29yay4gJiM4MjIwOzgmIzgyMjE7IGlzIGFuIGFjZXR5bCBncm91cCwgYXNzb2NpYXRlZCB3aXRoIGhpc3RvbmUgbW9kaWZpY2F0aW9uIHRoYXQgYWxsb3dzIHRyYW5zY3JpcHRpb24u[Qq]

[c]IEVudGVyIHdvcmQ=[Qq]

[f]IE5vLg==[Qq]

[c]ICo=[Qq]

[f]IE5vLiBGaW5kIHNvbWV0aGluZyB0aGF0JiM4MjE3O3MgYm9uZGVkIHdpdGggb25lIG9mIHRoZSBoaXN0b25lIHRhaWxzIChzaG93biBhdCAmIzgyMjA7NSYjODIyMTspLCBhbGxvd2luZyB0aGUgRE5BIHRvIHVuY29pbCBhbmQgYmVjb21lIGF2YWlsYWJsZSBmb3IgdHJhbnNjcmlwdGlvbi4=[Qq]

[q] In the diagram below, which LETTER is showing euchromatin?

[textentry single_char=”true”]

[c]IE I=[Qq]

[f]IE5pY2Ugam9iLiBCIGlzIHNob3dpbmcgZXVjaHJvbWF0aW4u[Qq]

[c]IEVudGVyIHdvcmQ=[Qq]

[f]IE5vLg==[Qq]

[c]ICo=[Qq]

[f]IE5vLiBMb29rIGZvciBhIGxldHRlciB0aGF0JiM4MjE3O3MgYXNzb2NpYXRlZCB3aXRoIGxvb3NlbHkgY29pbGVkIEROQS4=[Qq]

[q] In the diagram below, which LETTER is showing heterochromatin?

[textentry single_char=”true”]

[c]IE E=[Qq]

[f]IE5pY2Ugam9iLiAmIzgyMjA7QSYjODIyMTsgaXMgdGlnaHRseSBwYWNrZWQgaGV0ZXJvY2hyb21hdGluLg==[Qq]

[c]IEVudGVyIHdvcmQ=[Qq]

[f]IFNvcnJ5LCB0aGF0JiM4MjE3O3Mgbm90IGNvcnJlY3Qu[Qq]

[c]ICo=[Qq]

[f]IE5vLiBMb29rIGZvciBhIGxldHRlciB0aGF0JiM4MjE3O3MgYXNzb2NpYXRlZCB3aXRoIHRpZ2h0bHkgY29pbGVkIEROQS4=[Qq]

[q] In the diagram below, which number represents methyl groups?

[textentry single_char=”true”]

[c]ID Q=[Qq]

[f]IE5pY2UuICYjODIyMDs0JiM4MjIxOyByZXByZXNlbnRzIG1ldGh5bCBncm91cHMu[Qq]

[c]IEVudGVyIHdvcmQ=[Qq]

[f]IE5vLCB0aGF0JiM4MjE3O3Mgbm90IGNvcnJlY3Qu[Qq]

[c]ICo=[Qq]

[f]IE5vLiBMb29rIGZvciBhIG51bWJlciBpbmRpY2F0aW5nIHNvbWV0aGluZyB0aGF0IGNoZW1pY2FsbHkgbW9kaWZpZXMgRE5BIGFuZCBoaXN0b25lIHByb3RlaW5zIGluIGEgd2F5IHRoYXQgY2F1c2VzIEROQSB0byBiZWNvbWUgdGlnaHRseSBwYWNrZWQgaGV0ZXJvY2hyb21hdGluLg==[Qq]

[q] In the diagram below, which number represents an acetyl group?

[textentry single_char=”true”]

[c]ID Y=[Qq]

[f]IE5pY2UuICYjODIyMDs2JiM4MjIxOyByZXByZXNlbnRzIGFjZXR5bCBncm91cHMuIEFjZXR5bCBncm91cHMgbW9kaWZ5IGhpc3RvbmVzIGluIGEgd2F5IHRoYXQgY2F1c2VzIEROQSB0byB1bmNvaWwsIG1ha2luZyBnZW5lcyBhdmFpbGFibGUgZm9yIHRyYW5zY3JpcHRpb24u[Qq]

[c]IEVudGVyIHdvcmQ=[Qq]

[f]IFNvcnJ5LCB0aGF0JiM4MjE3O3Mgbm90IGNvcnJlY3Qu[Qq]

[c]ICo=[Qq]

[f]IE5vLiBIZXJlJiM4MjE3O3MgYSBoaW50OiBhY2V0eWwgZ3JvdXBzIG1vZGlmeSBoaXN0b25lJiM4MjE3O3MgaW4gYSB3YXkgdGhhdCBhbGxvd3MgRE5BIHRvIHVuY29pbCwgbWFraW5nIGdlbmVzIGF2YWlsYWJsZSBmb3IgdHJhbnNjcmlwdGlvbi4=[Qq]

[q] The functional group associated with silencing DNA is the [hangman] group.

[c]IG1ldGh5bA==[Qq]

[q] In female mammals, one of the two X chromosomes in every cell becomes deactivated, and can be seen as a piece of [hangman] called a [hangman]body.

[c]IGhldGVyb2Nocm9tYXRpbg==[Qq]

[c]IGJhcnI=[Qq]

[q] The functional group associated with activating DNA so that it can be transcribed is the [hangman] group.

[c]IGFjZXR5bA==[Qq]

[q] The tortoiseshell pattern of fur is explained by the fact that because of X chromosome [hangman] female mammals are, developmentally, [hangman].

[c]IGluYWN0aXZhdGlvbg==[Qq]

[c]IG1vc2FpY3M=[Qq]

[q multiple_choice=”true”] Extremely rarely, a male tortoiseshell fur pattern is found in a male cat. As adults, these cats are often sterile. Which of the following is the most likely explanation?

[c]VGhpcyBtYWxlIGNhdCBpbmhlcml0ZWQg YW4gZXh0cmEgWCBjaHJvbW9zb21lLg==[Qq]

[f]RXhhY3RseS4gQXMgbG9uZyBhcyB0aGUgY2F0IChvciBhbnkgbWFtbWFsKSBoYXMgYSBZIGNocm9tb3NvbWUuIEl0JiM4MjE3O3MgYSBtYWxlLiBCdXQgaWYgYSBwcm9ibGVtIGluIHRoZSBmYXRoZXImIzgyMTc7cyBzcGVybSBvciBtb3RoZXImIzgyMTc7cyBlZ2cgcmVzdWx0ZWQgaW4gYW4gZXh0cmEgWCBjaHJvbW9zb21lLCB0aGVuIG9uZSBvZiB0aGVzZSBYIGNocm9tb3NvbWVzIHdvdWxkIGJlY29tZSBhIEJhcnIgYm9keSwgYW5kIHRoZSBtYWxlIGNvdWxkIGRpc3BsYXkgdGhlIHRvcnRvaXNlc2hlbGwgcGF0dGVybi4=[Qq]

[c]QSByYW5kb20gcHJvY2VzcyBvZiBtZXRoeWxhdGlvbiBzaWxlbmNlZCB0aGUgb3JhbmdlIGNvbG9yIGluIHJhbmRvbSBwYXRjaGVzIG9mIGNlbGxzLg==[Qq]

[f]Tm8mIzgyMzA7WW91IGtub3cgdGhhdCB0aGUgdG9ydG9pc2VzaGVsbCBwYXR0ZXJuIGluIGZlbWFsZXMgaXMgY2F1c2VkIGJ5IG9uZSBvZiB0d28gWCBjaHJvbW9zb21lcyBiZWNvbWluZyBhIEJhcnIgQm9keS4gRmluZCBhIGNob2ljZSB0aGF0IHJlbGF0ZXMgdG8gWCBjaHJvbW9zb21lIGluYWN0aXZhdGlvbi4=[Qq]

[c]VGhlIGNhdCBoYXMgYW4gZXh0cmEgc2V0IG9mIGNocm9tb3NvbWVz[Qq]

[f]Tm8uIEJ1dCB5b3UmIzgyMTc7cmUgb24gdGhlIHJpZ2h0IHRyYWNrLiBBbiBlbnRpcmUgZXh0cmEgc2V0IG9mIGNocm9tb3NvbWVzIGlzIGFsbW9zdCBhbHdheXMgZmF0YWwgaW4gbWFtbWFscyAoYnV0IGl0IGRvZXMgaGFwcGVuIGluIHBsYW50cykuIFlvdSBrbm93IHRoYXQgdGhlIHRvcnRvaXNlc2hlbGwgcGF0dGVybiBpbiBmZW1hbGVzIGlzIGNhdXNlZCBieSBvbmUgb2YgdHdvIFggY2hyb21vc29tZXMgYmVjb21pbmcgYSBCYXJyIEJvZHkuIEZpbmQgYSBjaG9pY2UgdGhhdCByZWxhdGVzIHRvIFggY2hyb21vc29tZSBpbmFjdGl2YXRpb24u[Qq]

[/qwiz]

6. Epigenetic changes can be transmitted across generations

As we’ve seen above, many of the differences between different tissue types (muscle, skin, nerve, liver, etc.) can be explained through epigenetic mechanisms such as methylation, acetylation, and the resulting organization of DNA into euchromatin or heterochromatin. Astoundingly, some of these changes can also be passed on from one generation to the next.

The mechanisms behind intergenerational epigenetics are still being worked out. But just to get a sense of the phenomenon, read the passage below, adapted from Beyond DNA: Epigenetics, in Natural History Magazine, by Nessa Carey).

We talk about DNA as if it’s a template, like a mold for a car part in a factory. In the factory, molten metal or plastic gets poured into the mold thousands of times, and, unless something goes wrong in the process, out pop thousands of identical car parts.

But DNA isn’t really like that. It’s more like a movie script: with different directors, there are different outcomes.

That’s what happens when cells read the genetic code that’s in DNA. In the case studies that follow, it’s really important to remember that nothing happened to the DNA sequence of the people in these case studies. Their DNA didn’t change (mutate), and yet their life histories altered in response to environmental influences.

The Dutch Hunger Winter lasted from the start of November 1944 to the late spring of 1945. A German blockade resulted in a catastrophic drop in food availability to the Dutch population. More than 20,000 people had died by the time food supplies were restored in May 1945.

One of the first studied effects was on the birth weights of children who had been in the womb during that terrible period. If a mother was well-fed around the time of conception and malnourished only for the last few months of the pregnancy, her baby was likely to be born small. If, on the other hand, the mother suffered malnutrition only for the first three months of the pregnancy (because the baby was conceived toward the end of the terrible episode), but then was well-fed, she was likely to have a normal-size baby. The fetus “caught up” in body weight.

But there were long-term effects. The babies who were born small stayed small all their lives, with lower obesity rates than the general population. For forty or more years, those people had access to as much food as they wanted, and yet their bodies never got over the early period of malnutrition. More unexpectedly, the children whose mothers had been malnourished only early in pregnancy had higher obesity rates than normal. Recent reports have shown a greater incidence of other health problems as well, including effects on certain measures of mental health. Even though those individuals had seemed perfectly healthy at birth, something had happened to their development in the womb that affected them for decades after. Even more extraordinarily, some of these effects seem to be present in the children of this group, that is, in the grandchildren of the women who were malnourished during the first three months of their pregnancy. So something that happened in one pregnant population affected their children’s children.

Let’s consider a different human story. Schizophrenia is a dreadful mental illness, that, if untreated, can completely overwhelm and disable an affected person. Patients may present with a range of symptoms including delusions, hallucinations, and enormous difficulties focusing mentally. Individuals with schizophrenia are fifty times more likely to attempt suicide than healthy individuals.

Schizophrenia affects between 0.5 and 1 percent of the population in most countries. Scientists have known for some time that genetics plays a strong role in determining if a person will develop this illness. We know this because if one of a pair of identical twins has schizophrenia, there is a 50 percent chance that their twin will also have the condition. But why isn’t the figure 100 percent? How is it that two identical individuals can become so very different?

These stories are examples of epigenetics. Epigenetics refers to all the cases in which the genetic code alone isn’t enough to describe what’s happening—there must be something else going on as well. On a molecular level, epigenetics can be defined as the set of chemical modifications surrounding and attaching to our genetic material that change the ways genes are switched on or off, but don’t alter the genes themselves (Mr. W’s emphasis)

The “epi” in epigenetics is derived from Greek and means at, on, to, upon, over, or beside. The DNA in our cells is not some pure, unadulterated molecule. Small chemical groups can be added to specific nucleotide bases within DNA. Our DNA is also smothered in special proteins. These proteins can themselves be covered with additional small chemicals. None of these molecular amendments changes the underlying genetic code. But adding these chemical groups to the DNA, or the associated proteins, or removing them can alter the expression of genes. Sometimes, if these patterns of chemical modifications are put on or taken off at a critical period in development, the pattern can be set for the rest of our lives.

Think about it: if the DNA sequence were all that mattered, identical twins would always be identical in every way. Babies born to malnourished mothers would gain weight as easily as other babies who had a healthier start in life. And we would all look like big amorphous blobs because all the cells in our bodies would be completely identical. That’s because epigenetics is the mechanism by which cells with the same genetic code express different parts of it during development, becoming liver, muscle, brain, or any of the hundreds of other cell types in the human body.

Epigenetic mechanisms influence huge areas of biology, and the revolution in our thinking is spreading further and further into unexpected frontiers of life on our planet. Why can’t we make a baby from two sperm or two eggs, but must have one of each? What makes cloning possible? Why is cloning so difficult? Why do some plants need a period of cold before they can flower? Since queen bees and worker bees are genetically identical, why are they completely different in form and function? Why are virtually all tortoiseshell cats female? Why is it that humans contain trillions of cells in hundreds of complex organs, and microscopic worms contain about a thousand cells and only rudimentary organs, but we and the worm have the same number of genes? These questions, and many more, will be addressed through upcoming studies in this emerging science.

For a much deeper dive into epigenetics, I strongly recommend the Epigenetics resources at the Genetic Science Learning Center, University of Utah.

7. Eukaryotic Gene Regulation through Epigenetics Flashcards

[qdeck style=”width: 600px !important; min-height: 400px !important;” bold_text=”false” qrecord_id=”sciencemusicvideosMeister1961-Epigenetics Flashcards (v2.0)”]

[h] Eukaryotic Gene Regulation Through Epigenetics

[q] What is epigenetics?

[a] Epigenetics involves control of gene expression that occurs above the level of DNA. Epigenetics mostly involves the way that DNA is packaged, and doesn’t involve changes in the DNA sequence. Epigenetics explains how cells in the same organism can have the exact same DNA, but be phenotypically different (such as the differences between the cells making up the lens of your eye, and cells making up muscle tissue). Epigenetic modifications can also be transmitted intergenerationally.

[q] What’s the difference between euchromatin and heterochromatin?

[a] Euchromatin is DNA that is loosely packaged and available for transcription. Heterochromatin is tightly packaged and not expressed.

[q] Identify the parts in the diagram below, and connect the diagram to euchromatin, heterochromatin, and gene expression.

[a] In the diagram below, 3 represents histone proteins, which together form a DNA packing unit called a nucleosome (6). Tightly packed (and therefore untranscribable) DNA is at 4. That makes all the DNA around 4 heterochromatin. “7” is loosely packed DNA. The loose packing is associated with the acetylation of a histone “tail” (at 8). The DNA around 7 would be euchromatin.

[q] Compare and contrast the roles of methylation and acetylation in gene expression.

[a] Methylated DNA (at 6) is tightly packed as heterochromatin and not transcribed. Acetylated DNA (or DNA associated with acetylated histones) (at 7) is loosely packed DNA that’s available for transcription.

[q] Explain what a “Barr body” is, and connect it to female mosaicism.

[a] A Barr body is an inactivated X chromosome. X inactivation is random and happens early in development, and once a cell’s X chromosome in inactivated, that pattern of inactivation is passed on to all of its descendants. As a result, females are developmental mosaics, with patches of cells with a paternal chromosome inactivated, and other cells with the maternal chromosome inactivated. Female mosaicism explains the tortoiseshell fur pattern in cats.

[/qdeck]

8. What’s next?

Proceed to Topics 6.5 – 6.6, Part 3: Eukaryotic gene regulation through control of transcription , the next tutorial in AP Bio Unit 6.