1. Sexual selection is based on the idea that certain phenotypes lead to higher reproductive success

Natural selection beautifully explains adaptations. But a quick look at many organisms reveals features that natural selection can’t, on its own, explain.

Let’s play a game called “Who’s male? Who’s female?

[qwiz qrecord_id=”sciencemusicvideosMeister1961-Who’s male, who’s female (v2.0)”]

[h]Who’s male? Who’s female?

[i]Here’s how to play. On the next cards, you’ll see males and females. Drag labels to correctly label each one.

[q labels = “top”]

[l]male

[fx] No, that’s not correct. Please try again.

[f*] Correct!

[l]female

[fx] No. Please try again.

[f*] Great!

[q labels=”top”]

[l]male

[fx] No. Please try again.

[f*] Great!

[l]female

[fx] No, that’s not correct. Please try again.

[f*] Good!

[q labels = “top”]

[l]male

[fx] No, that’s not correct. Please try again.

[f*] Good!

[l]female

[fx] No, that’s not correct. Please try again.

[f*] Good!

[/qwiz]

What you saw in each of the examples above is called sexual dimorphism. This is a condition in which the bodies of females and males within a species are different.

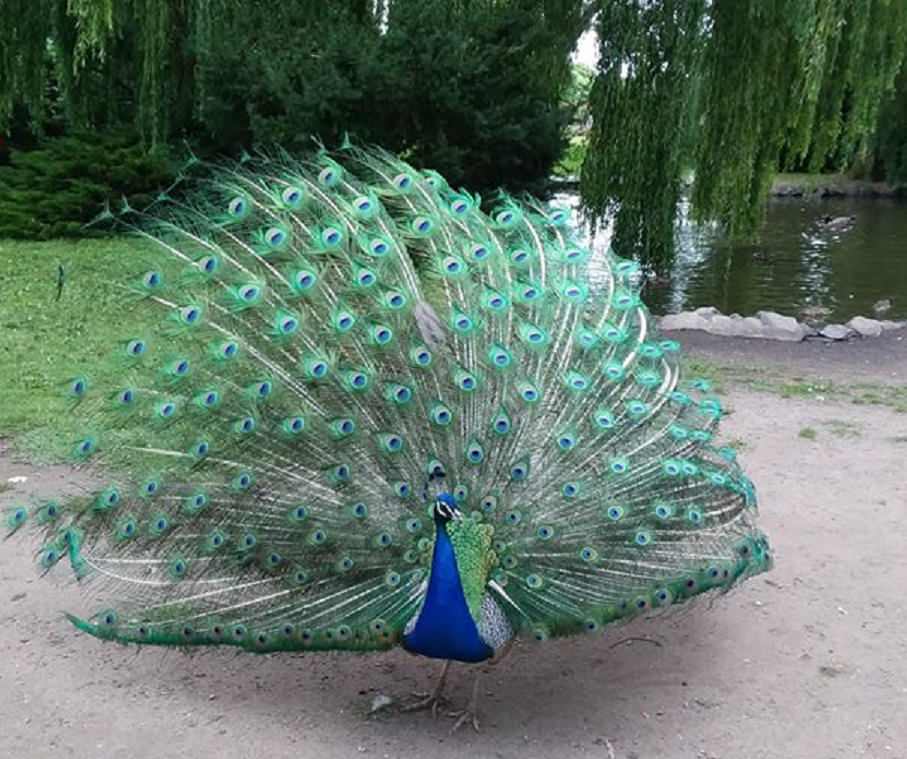

Note that some features connected with sexual dimorphism seem to run against the adaptations that come about through natural selection. The tail feathers of a peacock take energy to grow. They reduce a peacock’s speed on land and make flying harder. Similarly, an animal with bright coloration is easier for predators to spot. Why would these features evolve?

Sexual dimorphism isn’t found in all species. But it’s very prominent in some species. Why does it happen? If the members of a single species, whether male or female, are adapted to surviving a particular niche, why would they wind up having different features?

Sexual dimorphism comes about through a process called sexual selection. Whereas natural selection leads to adaptations, sexual selection leads to increased reproductive success.

Sexual selection was described by Darwin in 1879, so it’s not a new idea. However, it’s a very deep idea, and what’s below only scratches the surface. Also, keep in mind that the examples above and discussion below focus mostly on birds and mammals. In other animals, particularly insects and spiders, the drivers of sexual selection can be different and can bring about very different results. Just check out the males and females of the spider, Argiope appensa. Guess who’s male and who’s female this time.

[qwiz]

[h]Sexual dimorphism in Argiope appensa

[q labels = “top”]

[l]male

[fx] No, that’s not correct. Please try again.

[f*] Good!

[l]female

[fx] No, that’s not correct. Please try again.

[f*] Good!

[/qwiz]

If you want to go deeper, you can start by reading this article in the NY Times, How Beauty is Making Scientists Rethink Evolution.

2. Intersexual Selection

In our limited exploration of how sexual selection works, we’re going to divide sexual selection into two basic patterns.

In intersexual selection, members of one sex (typically females) choose mates of the other sex (typically males). This is called intersexual selection, and it leads to males like peacocks: colorful, and highly adorned.

To use a spectacular example, let’s focus on peacocks. The most spectacular feature that peacocks have (the males are peacocks, the females are peahens) is their train of tail feathers. Peahens seem to prefer males who have trains with more eyespots. How do we know? In a study of peacock mating behavior led by Marion Petrie, the number of eyespots in a male’s train of feathers was positively correlated with male mating success.

Let’s set some context. When it’s mating season for peacocks, here’s what happens. The description is from Sciencing peacock-features-8567066.

Beginning in mid to late spring, peacocks establish small territories in close proximity to one another in an arrangement known as a lek. They begin their courtship displays to attract the peahens, spreading their iridescent tail feathers in a fan shape, strutting back and forth, and shaking their feathers to produce a rattling noise to get the peahens’ attention. A peahen will walk through several territories of different males, examining their displays and feathers closely, before selecting a mate.

Petrie and her team observed peacock mating and quantified the results. Here’s an excerpt from Petrie’s 1991 paper.

On no occasion did a female mate with the first male that courted her and, on average, females visited three different males. Females thus always reject some potential mates. For 10 out of 11 sequences ending in successful copulation, the male “chosen” at the end of a sequence had the highest eye-spot number among the males visited. These data support Darwin’s hypothesis that the peacock’s train has evolved, at least in part, as a result of a female preference.

On top of this, scientists have experimentally manipulated peacock trains. In one experiment, Petrie and her team removed eyespots from peacock trains. The result: “Peacocks with eye-spots removed showed a significant decline in mating success …compared with a control group.” (Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology (1994) 34:212-217)

So think about what happens. Males and females become participants in a positive feedback system that results in the males’ extraordinary train of feathers. Females choose partners with longer tail feathers. The males who successfully mate pass on their genes for longer tail feathers, a trait that gets expressed in their male offspring. The females pass on their preference for longer male feathers, a trait that gets expressed in their female offspring.

How does this system begin in the first place? That is harder to explain. Choosy females are “looking” for evidence of fitness in their mates. A peacock who can produce a huge, brightly colored train of feathers must, from this perspective, be fit. But how does the process start? Earlier in this evolutionary process, any arbitrary difference that females start to find “attractive” might be selected for. Once the process begins, the positive feedback loop described above can lead to explosive evolutionary change.

Note that females are not only choosing physical traits but associated behaviors as well. Birdsong, courtship rituals, bower construction in bowerbirds, croaking in frogs, and firefly light patterns are behaviors that are all thought to be driven by intersexual selection.

3. Intrasexual selection

In some mating systems, competition between males for control of a harem of females or control of a breeding territory is the main driver of sexual dimorphism. Competition between members of the same sex for access to the other sex is called intrasexual selection.

The Northern Elephant seal is an example of a species in which this system is at work. These animals live off the coast of California. Like all seals, they come on shore to breed.

Because breeding sites are limited, a male who can control a breeding area will have access to all of the females in that area. That sets off an evolutionary dynamic in which males compete for control of breeding beaches. Who wins in a competition like this? Usually the larger and more aggressive male.

As with intersexual selection, a positive feedback loop ensues. Among elephant seals, males can be up to 13 feet long, and weigh over 4000 pounds. Females grow to be 10 feet long, but are less than half the mass of the males, averaging about 1300 pounds.

4. Sexual Selection: Checking Understanding

Again, sexual selection is a huge (and controversial) topic. Search for “sexual selection in humans” and you can go way down the rabbit hole. But for now, a quick check for understanding.

[qwiz qrecord_id=”sciencemusicvideosMeister1961-Sexual Selection (v2.0)”]

[h]Sexual selection

[i]

[q]Differences in form between the males and females of a species are called sexual [hangman].

[c]ZGltb3JwaGlzbQ==[Qq]

[q]Natural selection leads to [hangman]. Sexual selection leads to features that increase [hangman] success.

[c]YWRhcHRhdGlvbg==[Qq]

[c]cmVwcm9kdWN0aXZl[Qq]

[q]In [hangman] selection, members of one sex (typically females) choose whom they’ll mate with.

[c]aW50ZXJzZXh1YWw=[Qq]

[q]In [hangman] selection, members of one sex (typically males) compete with one another for reproductive access to the other sex.

[c]aW50cmFzZXh1YWw=[Qq]

[q]Male gorillas fight for control of a group of females. What kind of selection is at work?

[c]aW50ZXJzZXh1YWw=[Qq]

[c]aW50cmFz ZXh1YWw=[Qq]

[q]Male bowerbirds create highly decorated structures called bowers. Females examine these bowers. If they like them, they’ll mate with the male who made the bower. What kind of selection is at work?

[c]aW50ZXJzZXh1YW wgc2VsZWN0aW9u[Qq]

[c]aW50cmFzZXh1YWwgc2VsZWN0aW9u[Qq]

[q]The difference in form between the male and female Goldie’s bird of paradise probably arose through what kind of selection?

[c]aW50ZXJz ZXh1YWw=[Qq]

[c]aW50cmFzZXh1YWw=[Qq]

[q]These elk are battling for dominance. What kind of selection is at work?

[c]aW50ZXJzZXh1YWw=[Qq]

[c]aW50cmFz ZXh1YWw=[Qq]

[/qwiz]

5. Flashcards: Seven Things to Know about Artificial, Natural, and Sexual Selection

[qdeck style=”width: 600px !important; min-height: 450px !important;” bold_text=”false” qrecord_id=”sciencemusicvideosMeister1961-Artificial, Natural, Sexual Selection Flashcards”]

[h] Seven things to know about Artificial, Natural, and Sexual Selection

[i]

[q] Through artificial selection, breeders have created hundreds of varieties of plants and animals suited to human purposes. Explain how artificial selection works.

[a] In artificial selection (or selective breeding), animal or plant breeders envision a desired trait in an animal or a plant. For many generations, breeders select individuals with that desired trait, allowing only those with the desired trait to reproduce.

In plant breeding, breeders select seeds from plants with the desired traits and use those seeds to sow the next crop. In the case of animals, breeders select males and females with the desired traits and breed them together.

[q]Define natural selection, and in five steps, explain how natural selection works.

[a]Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals of the same species due to differences in phenotype.

- In every population, there’s inherited variation.

- In every species, parents produce offspring at a rate that exceeds that environment’s ability to support them. In other words, many are born but few survive.

- The ones who survive will most often be those with beneficial traits.

- Ongoing mutation renews variation

- The process gets repeated generation after generation.

[q] What’s the relationship between individual organisms, selection, and evolution?

[a] Individual organisms are selected by the environment for survival and reproduction. Through repeated rounds of selection, populations become more adapted over time. Individuals are selected: populations evolve.

[q] From an evolutionary perspective, what is fitness?

[a] Fitness is a measure of the number of offspring that survive to reproduce.

[q] Why is mutation important to evolution?

[a] Mutation provides the variation upon which natural selection acts. Because of mutation, natural selection can be a creative force that shapes new adaptations (as opposed to a process that merely culls unfavorable phenotypes from a population).

[q]Compare and contrast natural selection and sexual selection.

[a]Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals of the same species due to differences in phenotype. Sexual selection can be thought of as a subcategory of natural selection: it’s the advantage that some members of one sex have over other individuals of the same sex solely in relation to reproduction.

[q]How does intersexual selection differ from intrasexual selection, and what kind of phenotypes does each one produce?

[a]In intersexual selection, one sex (often females) chooses mates of the other sex, selecting phenotypes that they find more attractive. Intersexual selection leads to males that are highly adorned, with bright colors or other features that can attract a female’s attention.

In intrasexual selection, members of one sex (typically males) compete with one another to control reproductive access to females, either through controlling a territory (e.g. elephant seals) or controlling a harem (e.g. gorillas, certain species of deer). Intrasexual selection selects for size, strength, and weaponry, and leads males who are large and aggressive (compared to females) and often have weapons such as horns or antlers that are used in male-against-male competition.

[x] [restart]

[/qdeck]

6. What’s Next?

Proceed to Topics 7.4 -7.5, Part 1: Understanding Allele Frequencies, the next tutorial in AP Bio Unit 7 (Evolution).