1. Introduction

In the previous tutorials, we’ve looked at variations on crosses that involved a single gene, with two alleles (or three, in the case of blood type). But what happens when two (or more) genes are being transmitted at the same time?

To see the answer, we’re going to look at the genetics experiments performed by Gregor Mendel in the 1850s and 1860s.

While Mendel’s life and career are outside the scope of AP Biology, you can learn more about his story on Wikipedia.

2. Mendel’s 1st Experiments: Monohybrid Crosses and Segregation of Alleles

The table below shows seven of the traits in garden peas that Mendel experimented with as he was figuring out the principles of genetics.

Why did Mendel work with peas? For one thing, they were easily available in true-breeding varieties. True breeding is roughly synonymous with homozygous. What it meant for Mendel is that a plant with yellow seeds could be crossed with another plant with yellow seeds and all the offspring would have yellow seeds. It’s similar to breeding a poodle with another poodle: the offspring will be poodles.

Mendel’s first series of experiments involved monohybrid crosses.

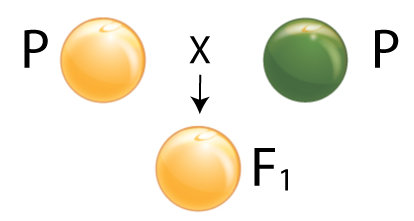

In these experiments, Mendel crossed varieties that differed in one trait. In other words, Mendel would cross a true-breeding pea plant with yellow seeds with one that had green seeds. The result would be a hybrid. In this context, hybrid is synonymous with heterozygous. In these crosses, Mendel called the parents the P generation (for parental) and the offspring the F1 generation. (F1 is for “first fillial.” “Fillial” means pertaining to sons or daughters, as in fillial piety).

In these experiments, Mendel crossed varieties that differed in one trait. In other words, Mendel would cross a true-breeding pea plant with yellow seeds with one that had green seeds. The result would be a hybrid. In this context, hybrid is synonymous with heterozygous. In these crosses, Mendel called the parents the P generation (for parental) and the offspring the F1 generation. (F1 is for “first fillial.” “Fillial” means pertaining to sons or daughters, as in fillial piety).

From our previous study of genetics, we can figure out what happened. The green-seed trait disappears in the first generation, so we can assume that green is recessive and yellow is dominant. As a result, all of the F1s are yellow heterozygotes.

The Punnett square (a mathematical tool that Mendel didn’t have at his disposal), looks like this.

| Y | Y | |

| y | Yy | Yy |

| y | Yy | Yy |

100% of the offspring are Yy: heterozygotes with yellow seeds.

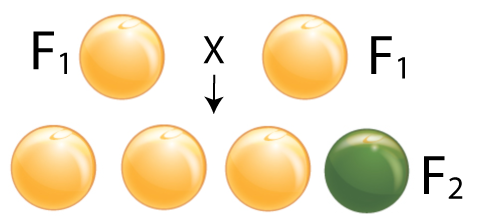

Mendel’s next move was a monohybrid cross. In a monohybrid cross, you cross two hybrids.

As we’ve previously seen when we were learning about sickle cell anemia, a monohybrid cross produces offspring in a 3 to 1 ratio, with 3 offspring showing the dominant trait for each one showing the recessive trait.

Here’s the Punnett square. We know that each of the F1s is a heterozygote.

| Y | y | |

| Y | YY | Yy |

| y | Yy | yy |

75% of the offspring have genotypes YY or Yy, giving them yellow seeds. 25% have green seeds (genotype yy).

Mendel’s monohybrid crosses revealed some of the key principles of genetics. These include the idea of dominant and recessive traits, and what Mendel called the principle of segregation. Why segregation? The name reflects Mendel’s insight that parents possess two alleles for a trait. When that parent creates offspring, he/she/it only passes on one of its two alleles. The alleles separate (or segregate) during gamete formation.

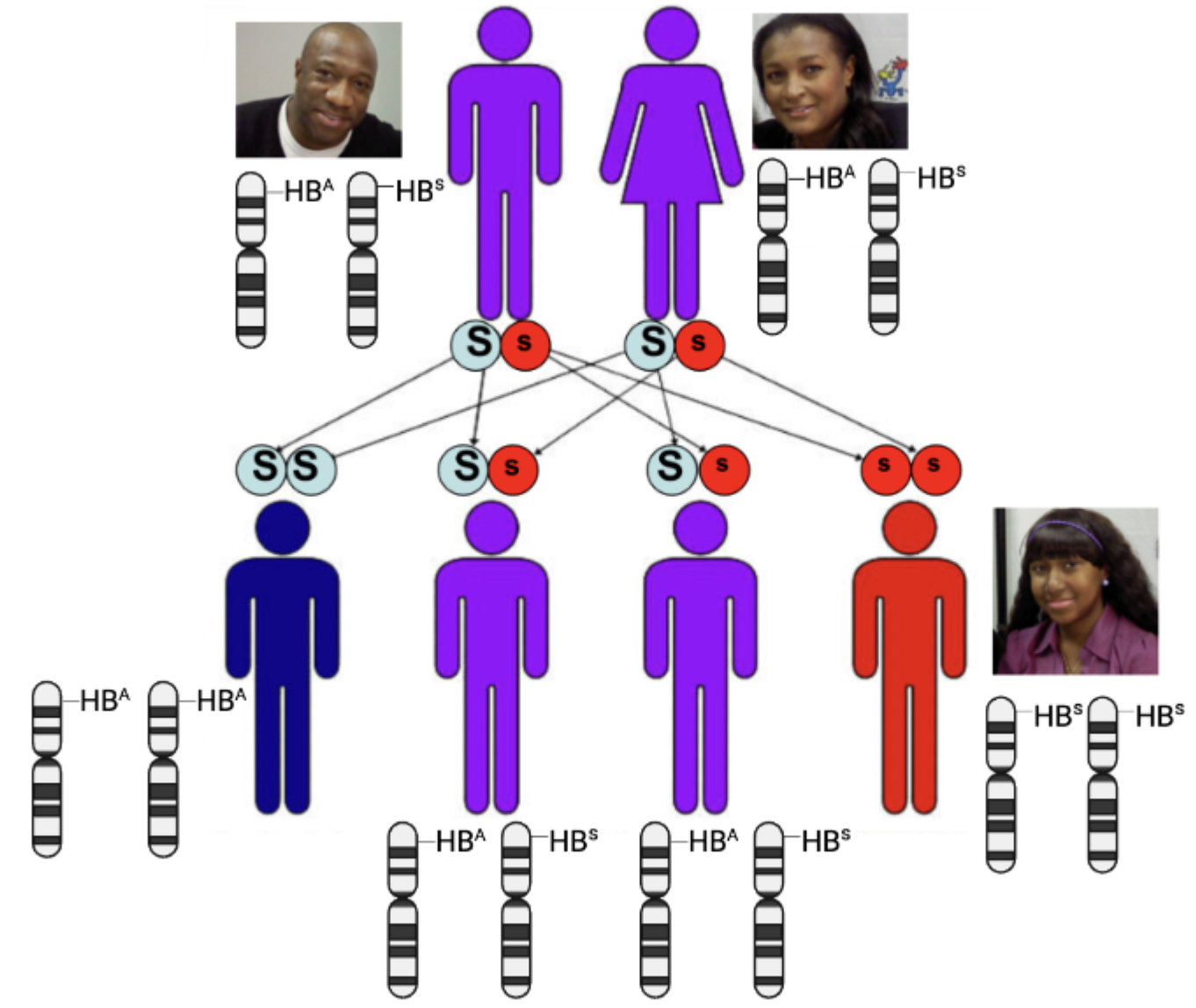

Note that we saw this in our introduction to genetics when we saw how sickle cell anemia can be inherited. Each of Hunter Haymore’s parents was a heterozygote carrier of the sickle cell allele. During meiosis, these alleles separated, with one of the two alleles sent to each parent’s gametes. That’s segregation of alleles.

3. Dihybrid Crosses and Independent Assortment

Mendel’s next series of experiments involved dihybrid crosses: crosses in which individuals were hybrid for two traits, such as stem height and flower color.

Follow what Mendel did through the interactive reading below.

[qwiz style=”min-height: 450px !important; width: 600px !important;” qrecord_id=”sciencemusicvideosMeister1961-Dihybrid Crosses, Interactive Reading (v2.0)”]

[h] Mendel’s Dihybrid Crosses Interactive Reading.

[q] We’ll start with seeing how Mendel produced his dihybrids. He started, as always, with true-breeding varieties. But these varieties were true-breeding for two traits. In this case, a pea plant that was true-breeding for tall stems and purple flowers was bred with a plant that was true-breeding for short stems and white flowers.

Predict what the offspring will be. When you’ve written your prediction in your student learning guide, click “continue.”

[q] All of the offspring were tall, with purple flowers. Note, however, that the offspring are dihybrid (hybrid tall stem AND hybrid purple-flowered)

[q] Mendel’s next move was to carry out a dihybrid cross: He crossed his F1 hybrids, producing the F2s. Predict what happened.

Click after you’ve written down your prediction.

[q labels = “right”]Here’s what happened. There were four phenotypes. And, once Mendel analyzed his data, he found that they occurred in predictable ratios. Try to predict which ratio goes with which phenotype. Don’t worry if you don’t know the answer. Just guess and drag these fractions until they’re in the right place.

[l]1/16

[f*] Correct!

[fx] No. Please try again.

[l]3/16

[f*] Excellent!

[fx] No. Please try again.

[l]9/16

[f*] Correct!

[fx] No. Please try again.

[q] So, here are the F2 results that you get from an F1 dihybrid cross.

- 9/16 have both dominant traits (in this case, tall stems AND purple flowers)

- 3/16 are dominant for the first trait and recessive for the second (tall stems, white flowers)

- 3/16 are recessive for the first trait and dominant for the second (short stems, purple flowers), and

- 1/16 are recessive for both traits (short stems, white flowers)

Explaining this 9:3:3:1 ratio got Mendel to his second great insight, his Principle of Independent Assortment. Let’s reconstruct Mendel’s thinking.

[q labels = “right”]Dihybrid cross results:

- Tall stem, purple flowers: 9/16

- Tall stem, white flowers: 3/16

- Short stem, purple flowers: 3/16

- Short stem, white flowers: 1/16

Let’s look at each characteristic separately.

If there were 16 offspring, you could expect ______ individuals to have tall stems; and ______ individuals to have short stems

Reducing that to a ratio you’d expect ______ with tall stems for every ______ with short stems.

Now, do the same for flower color. Out of 16, you’d expect ______ individuals with purple flowers; and ______ individuals with white flowers.

That’s a ratio of ______ with purple flowers to ______ white flowers.

[l]3/4

[f*] Great!

[fx] No, that’s not correct. Please try again.

[l]1/4

[f*] Great!

[fx] No, that’s not correct. Please try again.

[l]12

[f*] Great!

[fx] No. Please try again.

[l]4

[f*] Good!

[fx] No. Please try again.

[q] In the previous card, you determined that each trait separately has a 3:1 ratio of dominant phenotype to recessive phenotype (3 tall to 1 short; and 3 purple-flowered to 1 white flowered). That’s the ratio we’d expect for a monohybrid cross. But how do we explain the 9:3:3:1 ratio that we see when we combine these phenotypes? It’s the result that we’d get if we did two independent Punnett squares and then combined the results, using what’s called the rule of multiplication. Start by completing the Punnett squares below in your student learning guide.

Click to continue when you’re done.

[q] Here’s the solution:

Click when you’re ready.

[q] Now let’s talk about the rule of multiplication: when two events are independent, then the probability of them occurring together is the product of their independent probabilities. If I’m tossing a coin, the probability that four tosses will result in 4 heads is 1/2 x 1/2 x 1/2 x 1/2, or 1/16. Why? Because with each flip, the probability is 1/2, and these four events are independent.

Try this. Both the father and the mother in a family are heterozygous for cystic fibrosis (a recessive condition). They have two children. What’s the probability that both children will have cystic fibrosis? As you fill in the following blanks, you have to write out the numbers.

For the first child, the probability of being born with cystic fibrosis is one out of [hangman]. For the second child, it’s one out of [hangman]. That makes the probability for both children one over [hangman].

[c]IGZvdXI=[Qq]

[f]IEdyZWF0IQ==[Qq]

[c]IGZvdXI=[Qq]

[f]IENvcnJlY3Qh[Qq]

[c]IHNpeHRlZW4=[Qq]

[f]IEV4Y2VsbGVudCE=[Qq]

[q labels = “top”]Likewise, if we conclude (as Mendel did) that the trait for stem length operates independently from the trait for flower color, then the probability of a plant being tall AND purple-flowered is the product of a plant being tall (3/4), multiplied by the probability of it being purple-flowered (3/4). Use that logic to complete the table below.

| Probability of being Tall:

_______ |

Probability of having purple flowers:

__________ |

Probability of being tall, with purple flowers:

___________ |

| Probability of being Tall:

_______ |

Probability of having white flowers:

__________ |

Probability of being tall, with white flowers:

___________ |

| Probability of being short:

_______ |

Probability of having purple flowers:

__________ |

Probability of being short, with purple flowers:

___________ |

| Probability of being short:

_______ |

Probability of having white flowers:

__________ |

Probability of being short, with white flowers:

___________ |

[l]1/4

[f*] Correct!

[fx] No, that’s not correct. Please try again.

[l]3/4

[f*] Excellent!

[fx] No, that’s not correct. Please try again.

[l]9/16

[f*] Correct!

[fx] No. Please try again.

[l]3/16

[f*] Excellent!

[fx] No, that’s not correct. Please try again.

[l]1/16

[f*] Excellent!

[fx] No, that’s not correct. Please try again.

[q] So that’s Mendel’s principle of independent assortment, derived from the laws of probability.

However, we can also explain what happens in a dihybrid cross by thinking about meiosis, where there’s also a process called independent assortment. Look at the diagram below, and write down a quick explanation of meiotic independent assortment. When you’re done, check it against the next slide.

[q] Here’s an explanation of meiotic independent assortment: when homologous pairs are lined up on the cell equator during metaphase 1, the way each pair lines up is independent of every other pair. For example, in the diagram below, the chromosome that originated from the mother is pink; the one from the father is blue (sorry for the stereotypes). In cell A, the maternal chromosome of one pair is facing up, as is the paternal chromosome of the second pair. In cell B, the maternal chromosome for the first pair is facing up, and the maternal chromosome for the second pair is facing up. After anaphase 1 and cytokinesis, this will result in different arrangements of chromosomes in the haploid gametes. Note that there are no other arrangements of cells A and B that produce different results from what’s shown in cells 1 through 4.

With two homologous pairs, you get four possible arrangements of chromosomes in the gametes, as shown below.

[q] Genes are located on chromosomes. So if chromosomes are independently assorting, then so are the genes that are on these chromosomes (as long as these genes are on different chromosomes: we’ll look at what happens when they’re not in the next tutorial). To make this as simple as possible, look at the diagram below.

In this germ cell (a diploid cell that’s going to make haploid gametes), there are two homologous pairs of chromosomes. Because this was a dihybrid cross, we’re going to put a dominant allele (T or P) on one member of each homolog, and a recessive allele (t or p) on the other homolog.

Each gamete has to have an allele for stem length, and an allele for flower color. So, what alleles can be in each of the four gametes?

Figure out the four different combinations, write them down in your student learning guide, then check your answer on the next card.

[q] Here’s the germ cell, and the four gametes that it could produce by independent assortment. Note you can use the FOIL algorithm from algebra (First, Outside, Inside, Last) to get these results.

In the next slide, you can use these gametes to create a Punnett square. Click when you’re ready.

[q labels = “right”]In the dihybrid cross we’ve been examining, each of the parents can produce four types of gametes: TP, Tp, tP, and tP. That means that to predict the genotypes and phenotypes of the offspring, you need a 4 x 4 square to accommodate all the possible zygotes that can be produced.

I’ve set up the square below. Your job is to drag the right genotypes into the right spot.

| TP | Tp | tP | tp | |

| TP | _______ | _______ | _______ | _______ |

| Tp | _______ | _______ | _______ | _______ |

| tP | _______ | _______ | _______ | _______ |

| tp | _______ | _______ | _______ | _______ |

[l]TTPP

[f*] Great!

[fx] No. Please try again.

[l]TTPp

[f*] Great!

[fx] No, that’s not correct. Please try again.

[l]TtPP

[f*] Correct!

[fx] No, that’s not correct. Please try again.

[l]TtPp

[f*] Good!

[fx] No, that’s not correct. Please try again.

[l]TTpp

[f*] Excellent!

[fx] No, that’s not correct. Please try again.

[l]Ttpp

[f*] Correct!

[fx] No. Please try again.

[l]ttPP

[f*] Good!

[fx] No. Please try again.

[l]ttPp

[f*] Excellent!

[fx] No. Please try again.

[l]ttpp

[f*] Good!

[fx] No. Please try again.

[q labels = “right”] Here’s the Punnett square you completed on the previous slide. Let’s analyze the results to make sure we’re still seeing that 9:3:3:1 ratio.

- Drag a ♠ if the phenotype is Tall stem, Purple Flowers

- Drag a ♣ for Tall, white-flowered

- Drag a ♥ for short, purple-flowered

- Drag a ♦ for short, white-flowered

| TP | Tp | tP | tp | |

| TP | TTPP __ | TTPp __ | TtPP __ | TtPp __ |

| Tp | TTPp __ | TTpp __ | TtPp __ | Ttpp __ |

| tP | TtPP __ | TtPp __ | ttPP __ | ttPp __ |

| tp | TtPp __ | Ttpp __ | ttPp __ | ttpp __ |

[l]♠

[f*] Correct!

[fx] No, that’s not correct. Please try again.

[l]♣

[f*] Great!

[fx] No. Please try again.

[l]♥

[f*] Correct!

[fx] No. Please try again.

[l]♦

[f*] Good!

[fx] No, that’s not correct. Please try again.

[q] Here’s the table you produced on the previous slide.

| TP | Tp | tP | tp | |

| TP | TTPP ♠ | TTPp ♠ | TtPP ♠ | TtPp ♠ |

| Tp | TTPp ♠ | TTpp ♣ | TtPp ♠ | Ttpp ♣ |

| tP | TtPP ♠ | TtPp ♠ | ttPP ♥ | ttPp ♥ |

| tp | TtPp ♠ | Ttpp ♣ | ttPp ♥ | ttpp ♦ |

If you count up all the ♠ (tall, purple) you get [hangman] (please write out the number).

All the ♣ (tall, white) come to [hangman]

All the ♥ (short, purple) come to [hangman], and

All the ♦ (short, white) come to [hangman].

[c]IG5pbmU=[Qq]

[f]IEdvb2Qh[Qq]

[c]IHRocmVl[Qq]

[f]IEdyZWF0IQ==[Qq]

[c]IHRocmVl[Qq]

[f]IENvcnJlY3Qh[Qq]

[c]IG9uZQ==[Qq]

[f]IEdvb2Qh[Qq]

[/qwiz]

4. Solving Dihybrid Crosses and Related Problems

Mendel’s principle of independent assortment is important to know about in its own right. It’s also the basis of many dihybrid cross genetics problems that you’ll be asked to solve in an AP biology course.

In solving dihybrid cross problems, the toughest part, for most students, is figuring out the gametes that the parents can produce. Here’s an example, working with Mendel’s peas.

Try to solve these problems on your own before looking at the answer.

SAMPLE PROBLEM 1

In peas, round seed texture (R) is dominant over wrinkled seeds (r). Yellow seed color (Y) dominates over green (y). What is the genotype of an organism that is heterozygous round and heterozygous yellow? What gametes could this organism form?

Step 1: Figure out the genotype of the parents

The parent is described as heterozygous round and heterozygous yellow. That means it’ll be RrYy

Step 2: Use the FOIL algorithm to determine what gametes this parent can make.

FOIL (which I mentioned in the interactive reading above) stands for First, Outside, Inside, Last.

- “First” means the first allele in each pair. “R” is the first allele in “Rr,” and “Y” is the first allele in “Yy.” So, the first alleles in the genotype RrYy are RY. That’s the first possible gamete.

- Outside means the two outermost alleles. In RrYy that’s Ry. That’s the second possible gamete.

- Inside means the two innermost alleles. In RrYy that’s rY.

- Last means the two last alleles in each pair. In RrYy that’s ry

So, the four possible gametes are RY, Ry, rY, and ry.

SAMPLE PROBLEM 2

The setup is the same as in problem 1: In peas, round seed texture (R) is dominant over wrinkled seeds (r). Yellow seed color (Y) dominates over green (y). What is the genotype of an organism that is homozygous round and heterozygous yellow? What gametes could this organism form?

Step 1: Figure out the genotype of the parents

The parent is described as homozygous round and heterozygous yellow. That means it’ll be RRYy.

Step 2: Use the FOIL algorithm to determine what gametes this parent can make.

- “First” means the first allele in each pair. So, the first alleles in the genotype RRYy are RY. That’s the first possible gamete.

- Outside means the two outermost alleles. In RRYy that’s Ry. That’s the second possible gamete.

- Inside means the two innermost alleles. In RRYy that’s RY.

- Last means the two last alleles in each pair. In RRYy that’s Ry

If you list the four alleles derived using FOIL, you’ll see RY, Ry, RY, and Ry. The last two are repeats, which means that this parent can produce only two types of gametes: RY and Ry

SAMPLE PROBLEM 3

Let’s put these two problems together.

In peas, the allele for round seeds (R) is dominant over the allele for wrinkled seeds (r). Yellow seed color (Y) dominates over green (y). What is the result of a cross between a dihybrid Round Yellow parent and a parent that is homozygous round and heterozygous yellow?

STEP 1: Figure out the genotype of the parents. Look at problems 1 and 2 above. The genotypes are RrYy x RRYy.

STEP 2: Figure out the genotype of the gametes each parent can make.

Look at problems 1 and 2 above for the solution.

RrYy: RY, Ry, rY, ry

RRYy: RY and Ry.

STEP 3: Set up a Punnett Square.

In introducing dihybrid crosses, we used a Punnett square which was 4 squares x 4 squares, to accommodate all the possible gametes. But in the cross above, one parent can only form two types of gametes. So you can set up your Punnett square in a 4 x 2 grid, like this:

| RY | Ry | rY | ry | |

| RY | ||||

| Ry |

STEP 4: Complete your Punnett square by combining the alleles in the gametes to see the possible offspring.

| RY | Ry | rY | ry | |

| RY | RRYY | RRYy | RrYY | RrYy |

| Ry | RRYy | RRyy | RrYy | Rryy |

STEP 5: Analyze the offspring.

When we were doing monohybrid crosses, I had you list both the genotypes and phenotypes of the offspring. With dihybrid crosses, you mostly have to report phenotypes and their frequency.

In this case, the analysis is simplified because none of the offspring are wrinkled, so there are only two phenotype categories. I’m going to put a ♥ in all the squares with offspring that are round and yellow (R_Y_) and a ♦ in all the squares that have offspring that are round and green (R_yy).

| RY | Ry | rY | ry | |

| RY | RRYY♥ | RRYy♥ | RrYY♥ | RrYy♥ |

| Ry | RRYy♥ | RRyy♦ | RrYy♥ | Rryy♦ |

75% of the offspring are round and yellow

25% of the offspring are round and green.

5. Practice Problems

Solve the following problems in your student learning guide. Then flip the card to check your answer.

[qdeck bold_text=”false” style=”width: 600px !important; min-height: 400px !important;” qrecord_id=”sciencemusicvideosMeister1961-Dihybrid Crosses Practice Problems (v2.0)”]

[h] Dihybrid Cross Problems (Problems 1, 2, and 3 were the sample problems above).

[i] Biohaiku

Dihybrid Crosses

Independent Assortment

Genes flowing through time

[start]

[q] Problem 4: In peas, the allele for round seeds (R) dominates over wrinkled seeds (r). Yellow seed color (Y) dominates over green (y). What is the genotype of an organism that is homozygous wrinkled and homozygous yellow? What would be the possible genotypes of its gametes?

[a] The genotype of the homozygous wrinkled and homozygous yellow parent is rrYY. It can only produce one type of gamete: rY.

[q] Problem 5: In peas, the allele for round seeds (R) dominates over wrinkled seeds (r). Yellow seed color (Y) dominates over green (y). Cross a homozygous round, heterozygous yellow plant with one that is heterozygous round and homozygous green. What are the phenotypes of the offspring?

[a] Step 1: Genotypes of the parents: RRYy x Rryy

Step 2: Genotypes of the parents’ gametes: RRYy can create gametes RY and Ry. Rryy can create gametes Ry and ry.

Steps 3 and 4: Punnett square

| RY | Ry | |

| Ry | RRYy | RRyy |

| ry | RrYy | Rryy |

STEP 5: Results

1 round and yellow: 1 round and green

[q] Problem 6: In watermelon, green (G) is dominant over striped (g). Short (S) is dominant to long (s). What is the genotype of an organism that is heterozygous green and heterozygous short?

[a] Heterozygous green and heterozygous short is genotype GgSs

[q] Problem 7: In watermelon, green (G) is dominant over striped (g). Short (S) is dominant over long (s). Create a Punnett square showing a dihybrid cross, and list the frequency of each phenotype.

[a] STEP 1: Parental genotypes are GgSs x GgSs

STEP 2: Both parents will produce gametes GS, Gs, gS, and gs.

STEPS 3 and 4: Punnett Square

| GS | Gs | gS | gs | |

| GS | GGSS | GGSs | GgSS | GgSs |

| Gs | GGSs | GGss | GgSs | Ggss |

| gS | GgSS | GgSs | ggSS | ggSs |

| gs | GgSs | Ggss | ggSs | ggss |

STEP 5: 9 Green short, 3 green long, 3 striped short, 1 striped long

[q] Problem 8: In humans, the gene for normal skin color (A) is dominant to the gene for albino skin (a). The gene for achondroplasic dwarfism (D) is dominant to the gene for normal height (d). Both genes are autosomal. A heterozygous normal skin and heterozygous achondroplasic man has children with a heterozygous normal skin woman of normal height. What are the resulting phenotypes?

[a] STEP 1: Parental Genotypes: AaDd (father) x Aadd (mother)

STEP 2: Genotypes of gametes: AD, Ad, aD, ad for the father; Ad and ad for the mother.

STEPS 3 and 4: Punnett Square

| AD | Ad | aD | ad | |

| Ad | AADd ♥ | AAdd ♠ | AaDd ♥ | Aadd ♠ |

| ad | AaDd ♥ | Aadd ♠ | aaDd ♣ | aadd ♦ |

Using

- ♠ if the phenotype is normal skin, normal height (A_dd)

- ♣ for albino, achondroplasic (aaD_)

- ♥ for normal skin, achondroplasic (A_D_)

- ♦ for albino, normal height (aadd)

STEP 5: 3 Normal skin, achondroplasic ♥; 3 normal skin normal height ♠; 1 albino, normal height ♦, 1 albino achondroplasic ♣.

[q] Problem 9: In humans, the gene for normal skin color (A) is dominant to the gene for albino skin (a). The gene for Achondroplasic dwarfism (D) is dominant to the gene for normal height (d). A homozygous normal-skin homozygous achondroplasic man has children with an albino normal height woman. What are the resulting phenotypes?

[a] STEP 1: Parental Genotypes: AADD x aadd

STEP 2: Genotypes of gametes: AD for parent 1 (father); ad for parent 2 (mother)

STEPS 3 and 4: Punnett Square

| ad | |

| AD | AaDd |

STEP 5: 100% of offspring are AaDd

STEP 6: 100% of offspring are normal skin achondroplasics.

[/qdeck]

6. What’s next?

Continue to Topic 5.3 – 5.5 part 5: Linkage and Recombination (the next tutorial in AP Bio Unit 5)